Across Europe and the UK, many households believe they’ve cracked the code on cutting heating costs: crank the radiators right down, or even switch them off completely, every time they step out. The logic sounds unbeatable. Yet heating specialists say this “obvious” move often backfires, leaving homes colder, bills higher and systems under strain.

The big mistake: turning everything down too far

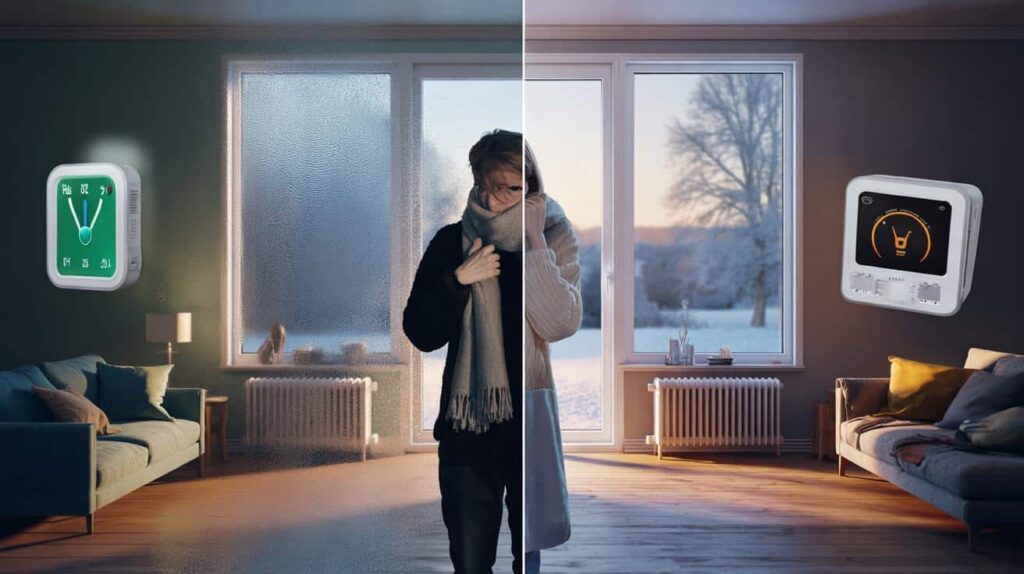

When frost starts to bite, energy anxiety kicks in. People leave for work and twist their thermostats right down. They head away for a day or a weekend and cut the heating completely, convinced every unused degree is a saving.

The reasoning looks simple: no one at home, no need to heat. But the physics of buildings tells a different story. A home that gets too cold doesn’t just feel unpleasant when you walk back in. It becomes a thermal sponge that has to be reheated from the ground up.

Meteorologists warn early February may bring an Arctic disruption outside historical norms

Meteorologists warn early February may bring an Arctic disruption outside historical norms

Slamming the heating right down can turn a day out into a marathon reheat that burns through more gas or electricity than you saved.

Walls, floors, ceilings, furniture and even carpets all store heat. Let them cool too much and your boiler, heat pump or electric radiators must work flat out to warm everything again, not just the air. That energy spike often cancels out – or even outweighs – the modest savings made during the absence.

Why experts favour small drops, not brutal cuts

Heating professionals now give a clear rule of thumb: lower the temperature, but not drastically, when you’re out for the day.

For short absences, specialists generally recommend cutting the set temperature by only 2–3°C, not shutting the heating down.

If you keep your home at 20°C when you’re in, shifting to 17–18°C while you are away for work is usually enough. That small gap holds several benefits:

- the home cools slowly, limiting heat loss

- walls and furniture stay mildly warm, so reheating is faster

- your system avoids working at full power for long stretches

- you reduce condensation and that “damp cold” feeling on your return

This gentle approach contrasts with the all‑or‑nothing mindset that leads to daily thermal shocks. By stabilising the temperature in a narrower band, you ease the load on your boiler or heat pump and keep comfort levels more consistent.

What really happens when your home gets too cold

The “turn it off, save money” idea ignores how buildings behave. Once your living room drops below a certain point, three things start to stack up against you:

1. Heavy structures act like ice blocks

Brick, concrete and stone have high thermal mass. If they cool down, they behave like giant cold batteries. When you arrive home and whack the thermostat back up, your heating system has to pump out heat for hours just to warm the structure, not just the air you feel.

2. Condensation and damp creep in

Cold surfaces attract moisture from the air. That’s when you start seeing mist on windows, clammy walls and that slightly musty smell. Over time, this extra moisture can encourage mould growth and damage paint or plaster.

3. You overcompensate in discomfort

Most people respond to a freezing house by boosting the thermostat higher than usual “just to catch up”. They may open hot radiators in unused rooms or leave the heating blasting late into the night. Those reactions add another layer of waste.

A home that never drops too far below its comfort temperature is easier, cheaper and healthier to heat than one that swings from chilly to roasting every day.

The thermostat trick that quietly does the job

Heating experts keep pointing to the same tool: a basic programmable thermostat or smart control. It doesn’t have to be flashy or expensive to pay for itself quickly.

A simple programmable thermostat can:

- lower the temperature by 2–3°C while you’re at work

- bring the heating back up shortly before you return

- keep rooms from falling below around 16°C during everyday absences

- switch to “frost protection” mode only for longer trips

This type of automation strips out human forgetfulness. You avoid leaving the heating blasting pointlessly all day, but you also avoid walking into an icy living room and cranking everything to the maximum out of frustration.

How far can you drop the temperature safely?

Experts usually distinguish between different types of absence and give rough target temperatures:

| Situation | Recommended indoor temperature | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Typical workday absence (8–10 hours) | 17–18°C | Reduces consumption while keeping fast, efficient reheating |

| Short absence (evening out) | 18–19°C | Small drop, no noticeable comfort hit on return |

| Weekend away (2–3 days) | 16–17°C | Limits damp and protects the building fabric |

| Holiday of a week or more | 12–14°C or frost‑protection setting | Prevents freezing pipes and mould, while cutting costs |

The message from heating engineers is clear: everyday absences call for moderation, not a full shutdown. Only long trips justify large drops, and even then, not below frost‑protection levels in cold climates.

Comfort, health and the “feels like” factor

There’s also a human dimension. Comfort isn’t only about the number on the thermostat. It depends on humidity, air speed and radiant temperature – the warmth of surrounding surfaces.

People often feel cold in a 20°C room if walls and windows are chilly, yet feel fine at 18°C when surfaces stay warm and dry.

By avoiding deep cool‑downs of your walls and furniture, you raise that radiant temperature and reduce the temptation to heat the air to 21–22°C. That subtle shift can save several percent on your bill across a full winter.

Real‑life scenarios: where the “radical drop” goes wrong

Consider this simple case. Household A leaves home at 8am, turns the heating from 20°C down to 5°C, and comes back at 6pm. The house has dropped close to outdoor temperature. The boiler then runs almost non‑stop for hours to drag the building back to comfort by bedtime.

Household B leaves at the same time, but lets their programmable thermostat drop from 20°C to 17°C, then ramp back up to 20°C from 5.15pm. Their boiler runs lightly at lower power for a longer period, avoiding a huge spike in demand.

Household A feels frozen on arrival and often boosts the thermostat to 22°C “just for a bit”. Household B walks into a liveable space and rarely touches the controls. Over a season, that difference adds up.

Key terms that help you make sense of your bill

Two notions come up repeatedly in expert advice:

- Thermal inertia: the tendency of a building to resist changes in temperature. Heavy materials like stone or concrete have high inertia, meaning they cool and warm slowly. These homes gain more from gentle, continuous heating.

- Setback temperature: the slightly lower temperature you maintain while away or asleep. A sensible setback avoids both waste and deep cooling.

Once you understand those ideas, the trap of “I’ll just turn it right down and save a fortune” becomes easier to spot. For most modern homes, careful setbacks, not dramatic switch‑offs, give the best balance between comfort and cost.

Households combining moderate setbacks, decent insulation, and a simple programmable thermostat can often trim their heating bill by several percent without feeling any real sacrifice. Add habits such as closing shutters or curtains at night, blocking draughts and heating only lived‑in rooms, and the cumulative effect over one winter can be significant.