For decades, school textbooks have treated Mesopotamia as the unquestioned birthplace of urban life. Fresh research from eastern Europe now suggests that organised cities, with planned streets and public spaces, may have flourished hundreds of years earlier on the rolling plains of Ukraine and neighbouring regions.

Ancient Ukraine challenges an old story

In the east of Europe, on Ukrainian soil, a site first identified more than fifty years ago is back in the spotlight. A new wave of digs and analyses has revived a bold idea: that some of the earliest true cities might have been built here, not in the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates.

The settlements belong to the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture, a late Neolithic and Copper Age civilization that stretched across what is now Ukraine, Moldova and Romania between roughly 5,400 and 2,700 BCE. Long seen as rural villages, several of these sites now look suspiciously urban.

Recent work suggests some Cucuteni–Trypillia settlements housed thousands of people in carefully planned layouts long before Mesopotamian cities reached similar scale.

This claim unsettles a long‑standing storyline that treats the “urban revolution” as a phenomenon born almost exclusively in the Near East during the Bronze Age.

What makes a city, anyway?

Before shifting the cradle of urban life, archaeologists must agree on what counts as a city. The label is not just about size. It also involves planning, complexity and shared space.

- Population: a concentration of people far beyond a typical village

- Layout: streets or paths arranged in a regular pattern

- Public zones: open areas or buildings used by the community

- Specialisation: evidence of crafts, storage, possible elites or administrators

- Durability: occupation over many generations

On several Ukrainian sites, archaeologists now see many of these features. Rows of houses ring central spaces. Pottery workshops cluster in specific quarters. Storage pits and potential ritual buildings hint at organized management.

Inside the Cucuteni–Trypillia mega‑sites

The term “mega‑site” has become common for the largest of these settlements. Some covered hundreds of hectares and may have held 10,000 people or more at their peak — a startling figure for the fourth millennium BCE.

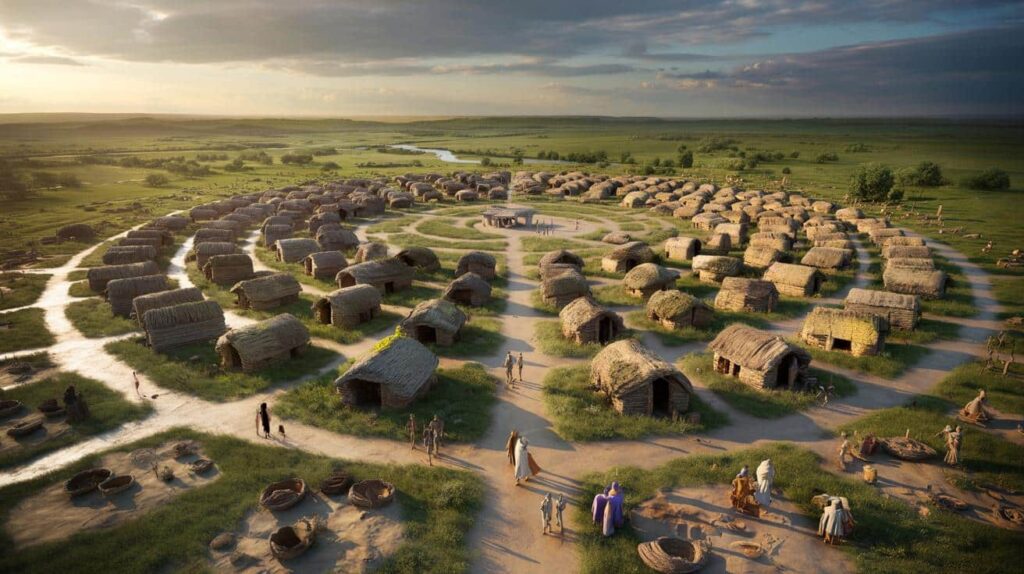

Many of these sites show a distinctive pattern: concentric circles or ovals of houses, sometimes several rings deep, cut by radial paths like spokes on a wheel. From the air, revealed by aerial photography or geophysical surveys, they look uncannily like planned suburbs.

House after house, arranged in repeating arcs, suggests a pre‑meditated urban blueprint rather than organic, haphazard growth.

Excavations reveal similar house sizes and layouts, built from wattle and daub, often with ovens and storage spaces. That relative uniformity hints at a society that valued a degree of equality, or at least avoided the stark social hierarchies seen later in Mesopotamian temple cities.

A rival timeline to Mesopotamia

For many historians, Mesopotamia has long stood as a primary cradle of civilization. Cities such as Uruk, with monumental temples, palaces and early writing systems, appear as the stars of this narrative.

The new findings from Ukraine do not erase that legacy. Instead, they push back the timeline for urban planning and suggest that large, complex settlements emerged independently in different regions.

| Region | Approximate peak of early cities | Key features |

|---|---|---|

| Cucuteni–Trypillia (Ukraine and neighbours) | c. 4,100–3,500 BCE | Mega‑sites, ringed layouts, large populations, craft production |

| Southern Mesopotamia | c. 3,500–3,100 BCE | Temple complexes, written records, clear elites and bureaucracy |

This overlap suggests that the shift to urban living was not a single “revolution” in one valley, but a broader process driven by similar pressures in different landscapes.

Why early cities appeared in eastern Europe

The Ukrainian plains may seem a surprising stage for early urban experiments, yet they offered key advantages. Fertile chernozem soils supported intensive agriculture. Rivers allowed movement of goods and people. Timber and clay were plentiful building materials.

Archaeologists suspect that population growth and expanding farming zones encouraged people to cluster in large communities. These hubs may have acted as seasonal centres at first, then evolved into permanently occupied settlements as networks tightened.

The mega‑sites might have served as huge gathering points for ritual, trade and decision‑making long before towns became year‑round homes.

Evidence of specialised pottery, figurines and possible long‑distance trade hints at shared cultural practices and economic ties across wide areas. Yet, unlike Mesopotamian cities, these eastern European settlements show little sign of sprawling temples or massive palaces.

Cities without kings?

One of the most striking aspects of the Cucuteni–Trypillia sites is the apparent absence of strong central authority. So far, researchers have not found monumental tombs, large royal residences or clear administrative quarters.

This has led some scholars to picture these early cities as relatively communal. Decision‑making may have rested with councils, family groups or religious leaders rather than dynastic kings.

The layout could reflect that. Instead of a palace at the centre, some mega‑sites place large open areas or modest ritual buildings in the middle. The city itself, with its dense ring of households, becomes the main monument.

Rethinking the “urban revolution”

The traditional story speaks of an urban revolution in the Levant and Mesopotamia during the Bronze Age: villages grow into cities, cities forge states, states create empires. The Ukrainian evidence complicates that simple line.

If large, structured settlements existed earlier in eastern Europe, then urban life did not require writing, bronze weapons or warrior kings. It could emerge from farming communities that reached a tipping point of population and complexity.

The first cities might have been less like miniature empires and more like oversized villages bound together by shared culture and mutual dependence.

This broader view changes how archaeologists read other regions too, from early towns in China to ceremonial centres in the Americas. Urbanism starts to look like a flexible set of strategies rather than a single, rigid package.

Key terms that reshape the debate

Several archaeological terms sit at the heart of this shift:

- Culture: in this context, a culture like Cucuteni–Trypillia refers to a group of communities that share common pottery styles, building habits and burial customs across a region.

- Mega‑site: an exceptionally large prehistoric settlement, often much bigger than typical villages of its time.

- Urban planning: deliberate design of streets, housing clusters and public spaces before or during construction, instead of buildings growing up randomly.

- Historiography: the way historians have previously written and structured the story of the past, including their assumptions and blind spots.

When researchers apply these ideas to Ukrainian sites, they find that many old assumptions about where cities “should” appear no longer fit comfortably.

What this means for future research

The debate over Ukraine’s early cities has practical consequences on the ground. Archaeologists now use finer‑grained surveys, soil analysis and dating techniques to understand exactly how long these mega‑sites were occupied and how they changed over time.

Computer simulations help test scenarios: could such dense populations survive on local farming alone? Did people cycle in and out seasonally? Were some rings of houses empty at any given moment, serving as reserves for growth or for rituals?

These models compare different possibilities and show which ones match the physical evidence. For instance, a fully occupied mega‑site year‑round would demand huge amounts of firewood and grain, putting pressure on nearby forests and fields. Signs of environmental stress could support that picture.

Why this matters beyond archaeology

Rethinking the first cities is not just an academic exercise. It changes how we view long‑term human behaviour. The Ukrainian case suggests that large, cooperative communities can function without strong kings or towering stone monuments, at least for a time.

Modern urban planners sometimes look to such examples for inspiration. Questions about shared space, decentralised decision‑making and resilience in the face of environmental limits echo through both past and present cities. Early eastern European settlements provide a rare, large‑scale test case of alternative ways to live together.