The French diver didn’t realize what he was filming at first. Just a strange, heavy-bodied fish, gliding slowly out of the night off the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, eyes shining like old coins in the beam of his lamp. His GoPro shook slightly as he tried to catch up, bubbles rising, heart racing, the seabed dropping away into blackness.

Then a guide grabbed his arm underwater, gave a frantic thumbs-up, and traced a huge fish shape with his hands. Later, on the boat, someone whispered the name almost like a superstition: coelacanth.

A fish that was supposed to be long gone.

A living fossil, suddenly very real.

A prehistoric shadow in the dive light

The French group had come to North Sulawesi for coral walls and turtles, not a 400-million-year-old survivor. The encounter happened on a deep technical dive, the kind that already pushes nerves: mixed gases, computers strapped to wrists, the rules of safe ascent ticking in your head.

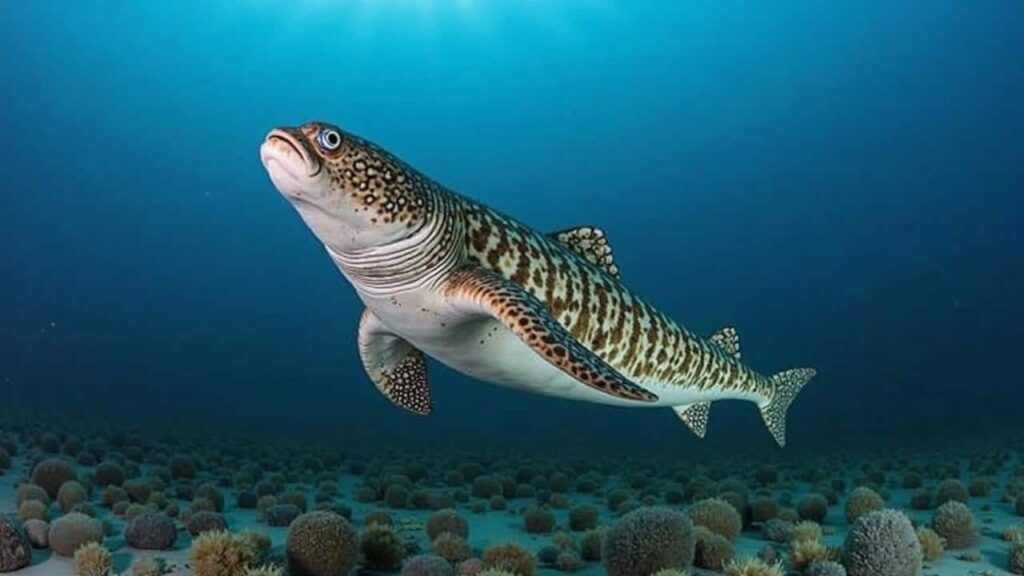

When the bulky blue-grey silhouette came into view, moving with an odd, almost clumsy grace, the mood flipped from routine to electric.

You can hear it in the muffled shouts captured on the video once they surface.

Back on shore, at a modest dive lodge framed by coconut trees, the divers replayed the footage on a laptop balanced between beer bottles and damp logbooks. Someone zoomed in on the thick, lobed fins, another on the white markings scattered across the rough skin like chalk stains.

The local dive guide, who had grown up in the nearby fishing village, shook his head slowly. He’d heard stories from older fishers of a “ghost fish” that came from the deep when storms churned the sea. He had never actually seen it.

Now it was staring back at him from a 13-inch screen.

One simple bathroom product is enough: why rats refuse to overwinter in gardens where it’s used

One simple bathroom product is enough: why rats refuse to overwinter in gardens where it’s used

Marine biologists would later confirm what the group already suspected: the images almost certainly show an Indonesian coelacanth, Latimeria menadoensis, the rarer cousin of the better known African species. Only described scientifically in 1999, this Indonesian line lives in steep, dark underwater canyons.

The species spends its days at depths where leisure divers rarely go, in cold, quiet water where sunlight fades and time feels slower. That’s one reason sightings are so scarce, and why each new video ricochets around scientific circles.

This new clip doesn’t rewrite evolution, but it does something almost as powerful: it makes the ancient suddenly personal.

Between wonder, Instagram, and fragile reality

The dive lodge owner, an Indonesian woman who has watched the region slowly transform from fishing outpost to bucket-list destination, saw what was coming the moment the clip hit social media. Booking requests jumped within days, many with the same breathless question: “Can we see the coelacanth too?”

Travel agencies in Europe started adding cautious references to “possible encounters with living fossils” in their promotional blurbs.

The quiet bay, lined with wooden houses and children playing in the shallows, was suddenly on the map in a new way.

One French diver from the group, a graphic designer from Lyon, found himself unexpectedly thrust into the role of minor celebrity. He gave interviews by Zoom between meetings, told and retold the story of the dive until the details blurred.

His phone filled with messages from strangers: some asking for technical tips to dive deeper, some begging for coordinates, some just writing “I’m crying, this is my dream.”

We’ve all been there, that moment when an incredible personal experience starts slipping out of your hands and into the hungry mouth of the internet.

The Indonesian authorities, who already juggle coral protection, fishing rights, and growing tourism, watched the buzz with mixed feelings. **Tourism money pays for patrol boats and school roofs**, but it also brings more boats, more anchors, more divers chasing the same rare moment.

Scientists worry that as the word “coelacanth” starts to trend, pressure will mount to push recreational divers closer to the fragile deep. Some operators are already hinting at “special expeditions”, flirting with depth limits that most bodies—and most insurance policies—are not built for.

Let’s be honest: nobody really reads all the pages of the dive waiver when chasing a dream.

Diving with a ghost from deep time, without breaking it

For the few who might actually cross paths with a coelacanth, the best “method” isn’t a secret spot, it’s restraint. The Indonesian species tends to lurk between 150 and 250 meters, way beyond ordinary recreational limits. That means the safest, least invasive encounters usually happen by accident at the shallow edge of its range, on technical dives planned for other reasons.

Respect begins long before you hit the water: choosing operators who won’t promise an encounter, who talk frankly about depth, decompression, and limits.

The coelacanth does not perform on demand.

Some divers, seduced by viral clips, are tempted to stretch their training or copy what they see on YouTube. That’s when small compromises start to pile up: a little deeper, a few minutes more, a second gas tank “just in case”.

The emotional hangover comes when you realize the animal you love might be harmed by the attention you helped create. Or when an accident at depth forces local communities to deal with the fallout.

*The ocean is already generous; it doesn’t owe us a prehistoric cameo on top of everything else.*

For scientists and conservation workers, the French group’s footage is both a gift and a warning label. It proves that the Indonesian coelacanth is still out there, sliding along volcanic slopes in the dark, but also that technology and tourism are closing the distance faster than our ethics sometimes do.

“Every new sighting is scientifically precious,” says a marine biologist involved with deep reef studies in the region. “But if we turn these animals into a checklist item for extreme divers, we risk loving them to death.”

- Choose dive centers that prioritize safety over “guaranteed” sightings.

- Ask where your money goes: reef fees, local guides, conservation projects.

- Resist sharing exact GPS locations of sensitive encounters.

- Support research groups monitoring deep-sea life around Sulawesi.

- Remember that **not seeing the rare thing** can be a sign you’re doing it right.

A living fossil in the age of notifications

The story of this French-Indonesian encounter says less about a single fish and more about the strange era we’re in. Evolution used to be an abstract diagram in a textbook; now you can watch 4K footage of a coelacanth on your lunch break, on the same screen where you read emails and doomscroll the news.

One species survived mass extinctions and continental drift, then slipped quietly through human centuries, only to be cornered by LEDs, algorithms, and cheap flights.

The people of North Sulawesi are standing at a crossroads that feels familiar in coastal communities worldwide. They are asked to host global dreams—of pristine reefs, rare encounters, perfect photos—while carrying the risk when things tip too far.

They know that with every new tourist dollar comes a harder question: how much of this deep, slow world can be safely shared, and how much must remain unseen to stay alive?

Somewhere below their boats tonight, beyond the reach of most dive lights and hashtags, coelacanths may be drifting along rocky ledges, jaws flexing gently as they wait for passing prey. They do not care that we call them “living fossils” or that a French diver’s shaky footage has made them briefly famous.

They have outlived empires and ice ages.

What they may not survive is our inability to sit with wonder without turning it into a product.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Coelacanths are extremely rare and deep-dwelling | Indonesian coelacanths usually live between 150–250 meters on steep underwater slopes | Helps set realistic expectations and avoids dangerous or unethical dive attempts |

| Tourism can both help and harm | Dive dollars can fund patrols and schools, but also create pressure for risky “guaranteed” encounters | Encourages more conscious choices about where and how you travel |

| Responsible behavior matters at every step | Choosing ethical operators, limiting depth, not sharing exact locations, backing research | Gives concrete ways for readers to enjoy marine wonders while supporting conservation |

FAQ:

- Is it really possible for tourists to see a coelacanth in Indonesia?

Yes, but it’s extremely unlikely. Most confirmed encounters are on deep technical dives around steep slopes in North Sulawesi, and even then there is no guarantee. Recreational divers almost never reach the depths where coelacanths spend most of their time.- Are coelacanths dangerous to humans?

No. Coelacanths are slow, deep-water predators that feed mainly on fish and squid. They tend to avoid lights and movement. The greater danger lies in humans pushing to unsafe depths or disturbing the animals, not the other way around.- Could increased tourism harm coelacanth populations?

Indirectly, yes. More boats and divers can bring pollution, noise, and habitat disturbance, especially if operators anchor near deep slopes or chase specific sightings. Pressure to offer “extreme” dives may also lead to more frequent incursions into their core habitat.- How can travelers support coelacanth conservation?

Travel with operators who talk openly about limits, ask about reef fees and local conservation projects, avoid demanding guaranteed wildlife encounters, and be careful about sharing precise locations online. Supporting credible marine research groups working in Sulawesi also helps.- Are coelacanths really unchanged for millions of years?

They are often called “living fossils” because their body plan looks similar to fossils hundreds of millions of years old. Still, they have continued to evolve in subtle ways. The term captures their ancient vibe, but evolution never completely stops.