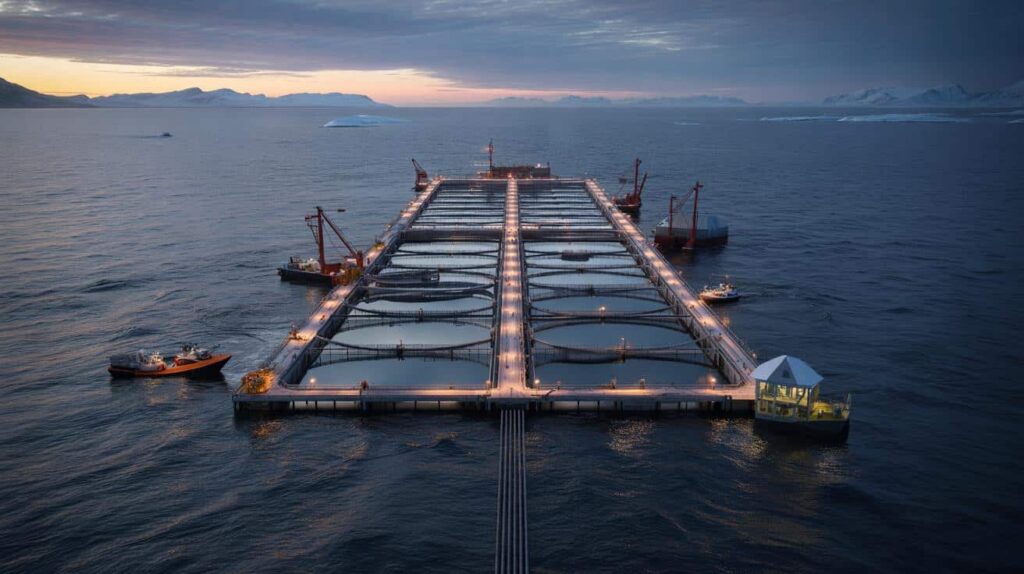

From the pier at Hadsel in northern Norway, it looks like a mirage. A long, low silhouette on the horizon, lit by tiny orange lamps, floating just where the steel-grey sea meets the sky. The fishermen in the harbour still call it “the ship”, even though it doesn’t sail anywhere. It just sits there, 385 metres of metal spine and salmon-filled cages, quietly rewriting what we think of as farming.

Tourists take out their phones. Locals look away a little faster.

Because once you understand what Havfarm is, you start to realise something else.

“I’ll buy it until I’m 90”: a dermatologist reveals the name of her favorite supermarket shampoo

“I’ll buy it until I’m 90”: a dermatologist reveals the name of her favorite supermarket shampoo

We’re changing the ocean without really moving a muscle.

When a “farm” looks like a supertanker

Seen up close from a service boat, Havfarm doesn’t behave like a normal structure. The platform stretches longer than three football pitches, its grid of walkways and cranes rising straight out of the swell. No barn, no tractors, no dirt under fingernails. Just the hiss of hydraulics, the hum of generators, and the slap of waves against steel.

Below the surface, six giant mesh pens hang down like submerged cathedrals. Inside them: millions of Atlantic salmon, gliding in slow, silver loops under computer surveillance. Everything is measured. Oxygen, feed, current, temperature. On a calm day it all feels almost too smooth, like someone put a spreadsheet on the sea.

The whole idea behind Havfarm is to move salmon farming away from crowded fjords and closer to open ocean conditions. Traditional coastal pens face algae blooms, parasites like sea lice, and conflict with neighbours who want clean, tourist-friendly shorelines. So Norway’s Nordlaks company decided to push offshore, into rougher waters where fewer people complain and the currents wash everything away faster.

Havfarm is anchored to the seabed with massive chains and can rotate with wind and waves. Its pens are deeper than many city apartment blocks are tall. Engineers designed it to withstand storm waves up to ten metres. That’s not a cosy little aquaculture site. That’s an industrial-scale attempt to domesticate a wild, moving landscape.

The logic is simple enough. Offshore, the risk of disease drops when water is colder and faster. The fish can swim more, which means better growth and firmer flesh. Feed is delivered with precision from control rooms that look more like air traffic towers than barns. Less medicine, fewer escapes, higher yields per cubic metre of water.

This is the promise that pulls investors, politicians, and curious journalists out onto the edge of the Arctic Circle. A structure that is not quite a ship, not quite a factory, not quite a farm.

A glimpse of what happens when our appetite for salmon meets our fear of empty supermarket shelves.

How you farm a moving animals in a moving sea

Running Havfarm day to day is less about rubber boots and more about dashboards. From a warm operations room, technicians watch live camera feeds inside each pen. Software tracks how fast the salmon rise to pellets, how densely they’re schooling, how much feed sinks uneaten. With that data, the system automatically adjusts rations to cut waste and lower the organic load falling to the seabed.

Every shift starts with small rituals. Coffee. A quick look at wind forecasts. A scan of lice counts and mortality numbers. It’s farming, but with headsets and spreadsheets instead of hay bales.

When storms hit, the romance disappears fast. The whole 385‑metre body groans as swells roll under it, and crew move clipped onto safety lines between feed silos and net edges. Divers wait days for waves to calm before they can go down to inspect moorings. On one winter trip, a worker described walking the length of the structure in sideways snow, squinting through a white blur to check for damage.

We’ve all been there, that moment when the job you thought would be sleek and modern turns out to be cold, heavy, and a little scary. Offshore salmon farming is no exception. The fish may be under algorithmic supervision, but the humans still get hit by the weather.

One quiet truth hangs over all this innovation: *the ocean does not care about our business plans*. Even with advanced modelling, currents don’t always flush waste the way engineers hoped. Wild fish gather under the pens, feasting on leftovers. Environmental groups worry about genetic mixing if farmed salmon escape during gear failures. And local communities ask whether these giant farms are really “out of sight” when they sit on migratory routes used for generations.

Let’s be honest: nobody really reads every environmental impact report before buying that discounted salmon fillet. Yet places like Havfarm force the question to the surface.

When your “farm” is the size of a skyscraper laid on its side, the margin for pretending it doesn’t exist gets very thin.

Choosing salmon in the age of mega-farms

There’s a simple, concrete gesture that changes how you relate to projects like Havfarm. Next time you pick up a pack of salmon, flip it over and actually read the production label. Look for hints: “Norwegian farmed”, “offshore”, certification logos like ASC or organic badges. Then ask yourself: where was this fish swimming six months ago? A sheltered fjord? A floating giant off the Lofoten Islands?

That tiny pause puts a real place behind the pink slice on your plate. Suddenly this 385‑metre steel beast in northern Norway isn’t just a news curiosity. It’s connected to your dinner.

People often feel guilty or paralysed when they start digging into food systems. Either you eat nothing with a footprint, or you shrug and eat everything. Both extremes burn out fast. A more humane way is to pick one or two habits and stick with them. Maybe you choose labelled, certified farmed salmon once a week instead of anonymous cheap trays. Or you balance farmed fish with small amounts of local wild catch.

The point isn’t to become a perfect consumer. It’s to remember that someone, somewhere, is walking down an icy steel walkway over deep water so that your fridge looks full.

“Standing on Havfarm, you realise the scale of our appetite,” a Norwegian deckhand told me, wiping sea spray off his glasses. “People want salmon all year, at a low price. This is what that looks like, out here, on a Tuesday in February.”

- Ask where it was raised

Country of origin and farming method give you a first, rough compass. - Look for credible labels

ASC, organic, or national eco-labels aren’t perfect, but they’re a step away from total opacity. - Vary what you eat

Rotating between farmed salmon, other species, and plant-based proteins spreads the environmental load. - Support transparency

Brands that show photos, maps, or farm names are usually under more pressure to behave responsibly. - Stay curious, not cynical

Curiosity keeps the conversation alive. Cynicism just gives the biggest players a free pass.

What Havfarm quietly says about us

Looked at from the right angle, Havfarm is less a story about fish and more a story about us. About how far we’re willing to go, and how deep we’ll drill into the sea, to keep familiar foods on familiar plates. A 385‑metre offshore farm exists because supermarket chillers expect reliable, uniform supply. Because sushi counters can’t have “out of stock” days. Because salmon has gone from holiday luxury to everyday protein.

Out on deck, with the mountains of Vesterålen fading into cloud, there’s a strange calm to this realisation. You see the cranes, the feed lines, the nets disappearing into dark water. You hear gulls and metal and nothing else. And you understand that behind every quiet slice of fish, whole landscapes are being quietly re‑engineered.

Not in a distant dystopia. Today. On a moving platform that looks like a ship, and isn’t.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Offshore scale | Havfarm is 385 metres long, with deep ocean pens holding millions of salmon | Helps you visualise the real size behind a “simple” farmed salmon fillet |

| Tech-driven farming | Cameras, sensors, and software manage feed, welfare, and waste in real time | Shows how digital tools are reshaping what food production looks like |

| Consumer power | Reading labels, choosing certifications, and varying species creates demand for better practices | Gives you small, concrete levers instead of abstract eco-anxiety |

FAQ:

- Is Havfarm really the world’s largest offshore salmon farm?Yes. At around 385 metres long, Havfarm is currently considered the largest offshore salmon farming structure, longer than many cruise ships and container vessels.

- Do the salmon in Havfarm live in cages or tanks?They live in large mesh pens that hang deep into the water below the platform. The fish experience natural currents and seawater, but inside controlled enclosures.

- Is salmon from Havfarm safer or healthier to eat?Havfarm aims to reduce disease and parasite pressure through offshore conditions and tight monitoring. From a consumer perspective, it’s still farmed salmon, so health aspects are similar to other regulated Norwegian farmed salmon.

- Does offshore farming solve environmental problems?It can ease some coastal issues like pollution hotspots and conflicts with tourism, and may lower parasite levels. Yet it brings new questions about escapes, wild fish interactions, and impacts on offshore ecosystems.

- How can I know if my salmon comes from a place like Havfarm?Check the packaging for origin (Norway, offshore references) and brand materials. Some producers showcase flagship sites like Havfarm in their marketing or websites, and certified products often offer more traceability details.