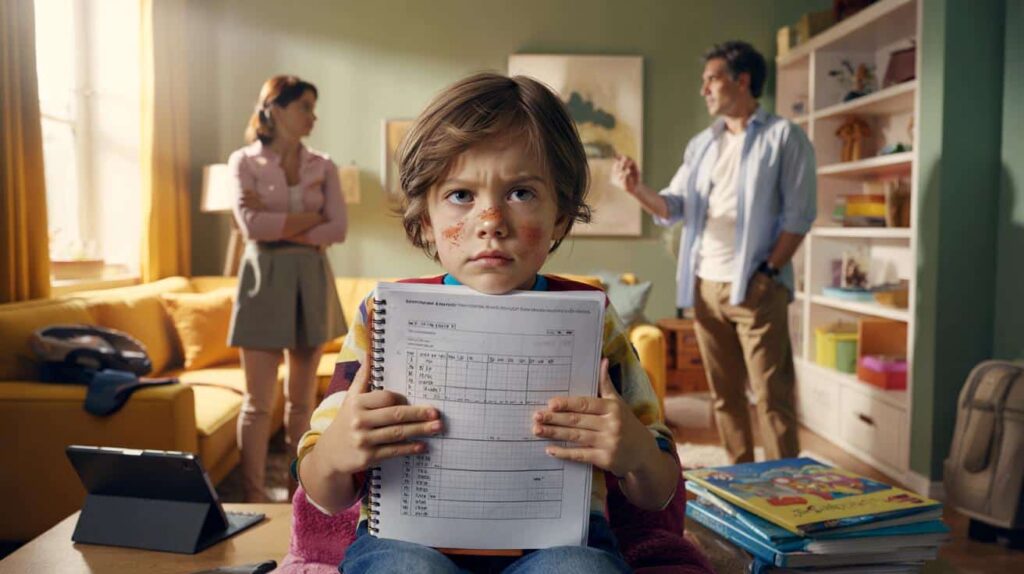

The boy at the playground had everything: the latest sneakers, a high-end scooter, a snack box worthy of Instagram. Yet he stood off to the side, shoulders tense, checking his parents’ faces more than the slide. Every time he laughed too loud, his mom’s eyebrows twitched. Every time he slowed down, his dad called out, “Come on, you can do better than that!”

Around them, other kids fell, cried, argued, made up. Life was messy and noisy and… alive. This child was like a little employee on a performance review. You could feel it in the way he scanned the adults before daring to be himself.

Walking away, I wondered: how many kids look happy on paper, but feel quietly miserable inside?

1. Demanding perfection from small humans

Psychologists have a word for it: “conditional approval.” Children who only feel lovable when they achieve, obey, or impress learn very early that mistakes equal danger. You see it in the kid who erases their homework five times, or in the little girl who cries if her drawing isn’t “beautiful enough.”

Probably F?15s, F?16s, F?22s And F?35s : Dozens Of US Jets Now Converging On The Middle East

Probably F?15s, F?16s, F?22s And F?35s : Dozens Of US Jets Now Converging On The Middle East

On the outside, perfectionist parenting can look like “high standards.” Smart, engaged, organized. On the inside, the child slowly learns that their value depends on their performance. Fun becomes a test. Rest becomes laziness. Childhood becomes a checklist.

Picture a 9-year-old who brings home a math test with a 19/20. Most of us know what happens next. The parent smiles quickly, then points at the missing point: “What happened here?”

A 2017 study in the journal *Psychological Science* followed children over years and found that parents’ perfectionism and criticism predicted increased anxiety and depression symptoms in kids. Not their grades, not their school, not their IQ. Their parents’ pressure.

The child hears, over and over, a quiet message: “You’re almost good enough. Almost.”

From a psychological angle, this sets up what’s called a “contingent self-esteem.” The child’s sense of self rises and crashes with every result. Fail a test, miss a goal, get a B instead of an A? Their whole identity takes the hit.

Over time, they may stop trying new things altogether. Better to never try than to try and disappoint. What looks like laziness is often fear in disguise. The more a parent makes perfection the standard, the more the child lives in silent terror of being truly seen as they are: messy, inconsistent, fully human.

2. Being emotionally absent while physically present

You can sit next to your child on the couch every evening and still feel light-years away from their inner world. Emotional absence is not about time, it’s about attention. It’s that parent who scrolls on their phone while mumbling “Uh-huh” to a story about recess. The dad who drives to practice, pays the bills, does everything right on paper, but rarely asks, “How are you really doing?”

Kids are radar. They feel when we’re there but not really there. Day after day, that gap becomes a quiet form of loneliness.

A teenager told a therapist, “My mom is always around, but we never actually talk. I could be doing drugs in the living room and she wouldn’t notice.” The mom would have been shocked to hear that. She cooked, cleaned, drove, answered emails about school. From her perspective, she was carrying the world.

Yet, when researchers study attachment, they see a pattern: children who grow up with emotionally unavailable parents often report higher levels of sadness, self-doubt, and a sense of being “invisible.” Not neglected in the obvious sense. Neglected in the subtle, emotional sense that leaves no bruises, only doubts.

Psychology describes this as a mismatch between the child’s emotional bids and the parent’s responses. The child says, “Look!” or “Guess what happened today!” What they’re really asking is, “Do I matter enough for you to step into my world for a minute?”

When the answer is often a distracted nod, over the years the child learns to stop sending bids. Their inner life goes underground. They stop sharing their small joys and small pains. Later, when bigger storms arrive, they’ve already trained themselves not to knock on the door. That’s how loneliness grows in a crowded home.

3. Constant criticism disguised as “helping them improve”

Some parents grew up in homes where love sounded like “Let me show you what you did wrong.” So they repeat it, convinced they’re preparing their child for a tough world. Correct the posture. Fix the tone. Edit the homework. Comment on the clothes. Guide, guide, guide, all day long.

From the child’s side, it feels like living under a microscope. They start to brace themselves whenever the parent opens their mouth. Not for warmth, but for the next “you should have…”

Imagine a 7-year-old proudly setting the table. The forks are on the wrong side, a glass is too close to the edge, the napkins are uneven. Instead of “Thank you, I love that you helped,” they get, “No, not like that. How many times do I have to tell you?”

One moment. One scene. Yet multiply it by hundreds of daily interactions and you build a soundtrack in the child’s head. Studies on “negative attribution bias” show that kids who receive frequent criticism tend to internalize a belief that they are fundamentally flawed or incompetent. They stop seeing the one thing they did right, because the spotlight always lands on the one thing they missed.

The logic behind constant criticism sounds reasonable: “If I don’t correct them, they’ll never learn.” The problem is tone and ratio. Psychology consistently suggests that children need a large base of safety and encouragement to tolerate and integrate feedback. Without that base, criticism doesn’t teach, it wounds.

Over time, these kids often become their own harshest critics. They get there before you do. Parents think, “They’re so mature and self-aware.” Inside, it’s usually just the internalized parent voice, running nonstop.

4. Overprotection that quietly steals resilience

Hovering over every step. Solving every conflict before it starts. Calling the teacher at the first sign of difficulty. At first glance, overprotective parenting looks like love turned up to the maximum. No scraped knees, no tough days, no tears if we can help it.

Yet psychology research is blunt: children who are overprotected tend to be more anxious, more fearful, and less confident in their own abilities. When you never get to test yourself against the world, the world becomes terrifying.

Think of a child whose parent always speaks for them. At restaurants, at the doctor, during playdates. The child reaches out and the parent gently steps in: “He’s shy, I’ll ask for him.” Over months and years, that kid’s social muscles simply don’t get used.

A large meta-analysis on “helicopter parenting” found that teens with overly involved parents report more depressive symptoms and a lower sense of autonomy. On paper, their lives look cushioned and safe. Inside, they feel fragile. Every decision feels like a cliff. They’ve never really had to say, “I can handle this.”

From a developmental point of view, small manageable failures are not a problem, they’re training. That lost soccer game, the forgotten homework, the awkward conversation at the birthday party, these are the emotional vaccines of childhood. They hurt a bit, they build a lot.

When parents rush in to erase every discomfort, they unintentionally send a powerful message: “You can’t handle this.” The child believes them. A few years later, that same child might refuse to try new hobbies, avoid challenges, or collapse at the first setback. Not because they’re weak, but because they never got to practice being strong.

5. Using shame and comparison as motivation

Some of the saddest sentences kids hear start with, “Look at…”

“Look at your sister, she never talks back.”

“Look at your cousin’s grades.”

“Look at how nicely those kids are sitting.”

Parents often think a little comparison will spark ambition. What it does more often is light a slow-burning shame. The child doesn’t just feel “not as good,” they start to feel wrong at the core.

A boy hears, “Why can’t you be more like your friend Tom, he’s so calm,” every time he bounces off the walls. Over the years, he stops seeing his energy as a trait to channel and starts seeing it as proof that he’s defective. A girl hears, “Your brother never has to be told twice” every time she forgets her bag. She’s no longer just forgetful. She’s “the difficult one.”

Research on social comparison and self-worth in children shows a repeated pattern: kids who are frequently compared to siblings or peers show lower self-esteem and higher internalized shame. They don’t just want to improve. They want to disappear.

Shame is different from guilt. Guilt says, “I did something wrong.” Shame says, “I am wrong.” When parenting leans on phrases like “You always…” or “You never…” combined with comparisons, it tilts heavily toward shame.

Here’s the plain truth: nobody grows into a happy adult by constantly hearing that someone else does life better than they do. That kind of message doesn’t motivate, it erodes. Over time, children may stop showing their real selves to avoid more comparisons, or they may turn the anger outward, attacking others before they can be judged again.

6. Never apologizing, even when you’re clearly wrong

Parents are human. They yell, they snap, they say things they regret. The problem isn’t the mistake itself, it’s what happens next. In many families, adults expect children to apologize, but rarely model it themselves. “Because I said so” becomes “Because I won’t say I was wrong.”

From a child’s perspective, that creates a strange world: adults can lose control and face no consequences, while kids are lectured about respect and responsibility. The result is often quiet resentment, plus a confusing sense of injustice.

Picture a father coming home stressed, barking at everyone for the noise, sending a kid to their room for something small. An hour later, he’s calm again, the house is quiet, dinner is on the table. Life moves on. Nobody talks about it. The child stays in their room, cheeks still hot, learning that their feelings are less important than keeping the peace.

Studies on “authoritarian” parenting styles show that warm authority combined with accountability builds trust, while rigid authority without repair tends to create distance and fear. Kids might obey. They rarely feel truly understood.

From a psychological lens, an apology from a parent does more than fix a moment. It tells the child, “Power doesn’t put you above decency.” It teaches humility as a living, breathing thing, not a word in a values poster.

*When parents never apologize, children either internalize blame (“It must be my fault”) or reject authority entirely as unfair.* Both options leave them less happy, less secure. A simple, sincere “I lost my temper earlier, and that wasn’t okay” can be a tiny act of emotional repair with a huge long-term impact.

7. Treating emotions as problems to shut down

Crying? “Stop it, there’s nothing to cry about.”

Angry? “Don’t you dare take that tone with me.”

Anxious? “Just relax, you’re overreacting.”

When parents respond to emotions with dismissal or irritation, children learn a fast lesson: some parts of you are welcome here, others are not. They start to edit themselves. Pleasant, calm, easy-going? Good. Sad, scared, frustrated? Dangerous.

Therapists often meet adults who struggle to name what they feel. When they dig into childhood, a common story appears: a parent who said things like “Big boys don’t cry” or “We don’t talk about that in this house.” The goal was often to keep the family functioning, to avoid drama, to stay strong.

Yet the research on emotional validation is crystal clear. Kids who are allowed to feel, name, and express their emotions in a safe way develop better emotional regulation and fewer internalizing problems like anxiety and depression. The ones who are constantly told to “toughen up” simply push everything inside.

From a psychological point of view, emotions are signals, not enemies. When a child’s feelings are consistently shut down, they don’t stop having those feelings. They stop trusting themselves. They learn that their inner radar is wrong or shameful.

Over years, this can create adults who either explode unexpectedly or go numb to cope. Neither path leads to a deep, grounded happiness. A child doesn’t need a parent who fixes every feeling. They need one who says, “I see you. This is hard. Let’s breathe together for a moment.”

How to shift these patterns without turning parenting into a guilt trip

Psychologists often say: repair beats perfection. You don’t need to redesign your entire parenting style overnight. Start with one tiny attitude shift at a time. Catch yourself the next time you go straight to criticism, and add one sentence of recognition first.

You might say, “You got 19/20, that shows real effort. Let’s look at the mistake together,” instead of jumping straight into “What happened here?” Small rephrasings change the emotional climate. They turn you from judge into ally. From there, everything else is easier.

Another gentle practice: replace comparisons with curiosity. When you’re about to say “Why can’t you be more like…”, pause and ask, “What made this hard for you today?” Kids relax when they feel investigated, not prosecuted.

Also, talk openly about emotions, including your own. “I was stressed earlier and I talked sharply, that wasn’t fair to you.” That kind of sentence doesn’t make you weak. It makes you credible. Let’s be honest: nobody really does this every single day. Yet doing it sometimes is already a massive upgrade from never doing it at all.

“Children don’t need perfect parents. They need parents who are willing to notice, adjust, and reconnect.” – Common summary of decades of attachment research

- Notice the pattern

Pause when you hear your “automatic” parenting voice and ask where it really comes from. - Name what you value

Tell your child specifically what you appreciate about them beyond grades or behavior. - Repair after rupture

Circle back after tense moments and talk briefly about what happened. - Allow small struggles

Let your child handle age-appropriate challenges without rushing in. - Protect space to talk

Even 10 distraction-free minutes a day can re-anchor connection.

Parenting attitudes that grow or crush joy: a wider look

If you recognize yourself in some of these attitudes, that doesn’t make you a “bad parent.” It makes you a parent shaped by your own story, your own wounds, your own culture. Psychology doesn’t hand out verdicts, it offers mirrors. Sometimes those mirrors sting a little, because they show what our kids may feel but don’t yet have words for.

What tends to create unhappy children, across many studies and stories, is not one bad day or one mistake. It’s a repeated atmosphere: constant pressure instead of support, control instead of guidance, silence instead of listening, shame instead of curiosity. The tone of the house. The way conflicts end. The way joy is allowed or trimmed.

On the flip side, kids who grow up feeling seen, heard, and allowed to be imperfect usually carry a quiet kind of strength. They still face anxiety, heartbreak, and big questions. Their lives are not magically easy. They just don’t have to fight an extra internal war at home.

Maybe the most powerful parenting shift is this: moving from “How do I get my child to behave?” to “How do I help my child feel safe enough to grow?” The answer will look different in every family. Yet the conversation itself already changes the air that children breathe.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Perfectionism hurts | Constant pressure and conditional approval raise anxiety and crush confidence | Helps parents understand why “high standards” can backfire emotionally |

| Connection beats control | Emotional presence, apologies, and validation build secure attachment | Offers a concrete focus for everyday interactions with children |

| Small changes matter | Rephrasing, repairing, and allowing small struggles shift family dynamics | Shows that parents can act today without being flawless or starting from zero |

FAQ:

- Question 1How do I know if I’m putting too much pressure on my child?

- Answer 1Watch their body language and mood. If achievements bring more relief than joy, if they seem terrified of mistakes or hide their grades, the pressure may feel heavy to them, even if you think you’re being “reasonable.”

- Question 2Is it really harmful to compare siblings sometimes?

- Answer 2Occasional, gentle comparison might slip out, but frequent or pointed comparisons tend to create rivalry and shame. Focusing on each child’s unique strengths is far more protective for their self-esteem.

- Question 3What if my parents never apologized to me, and I don’t know how?

- Answer 3Start simple and short: “I shouted earlier, and I regret that. You didn’t deserve it.” You don’t need a speech. Just naming what happened and acknowledging the impact already feels huge to a child.

- Question 4Can I be too validating of emotions and end up “spoiling” my child?

- Answer 4Validation doesn’t mean giving in to every demand. You can say, “I see you’re upset we’re leaving the park” and still leave. The feeling is welcomed, the limit stays. That balance builds resilience.

- Question 5Where do I start if I recognize many of these patterns in myself?

- Answer 5Pick one small practice for a week: listening without interrupting for five minutes a day, or apologizing after you lose your temper. Consistency beats intensity. Over time, these tiny shifts rewrite the emotional script at home.