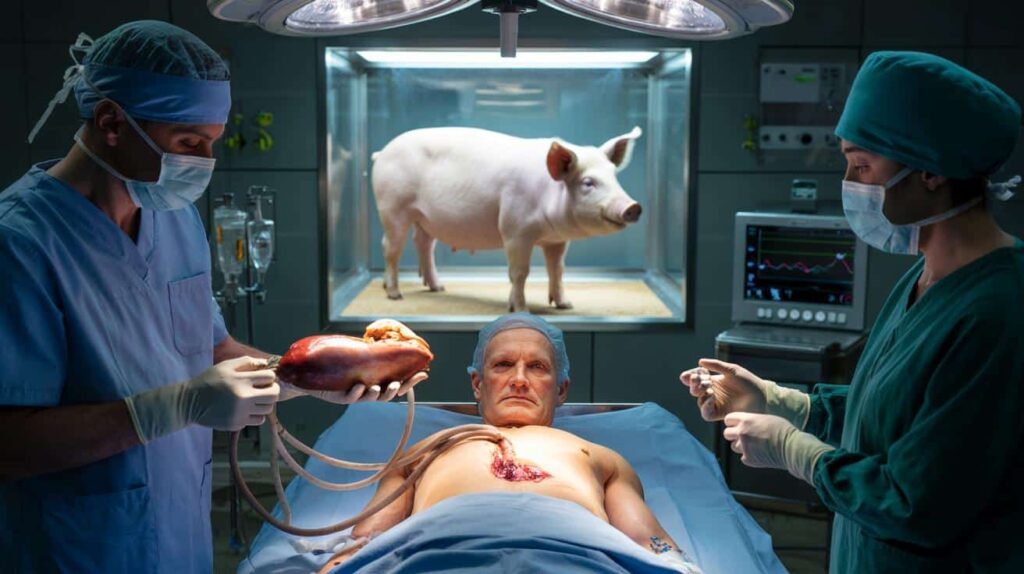

Behind operating theatre doors, surgeons and scientists are betting that pigs could help solve one of medicine’s most brutal shortages: the lack of human organs. Their aim is simple and radical at the same time – keep patients alive long enough to stop transplant waiting lists from becoming a death sentence.

The hidden crisis behind transplant waiting lists

Across Europe, the US and much of the world, demand for organs has outgrown the number of human donors by a wide margin. Campaigns urging people to carry donor cards help, but they do not close the gap.

If the ATM keeps your card, this fast technique instantly retrieves it before help arrives

If the ATM keeps your card, this fast technique instantly retrieves it before help arrives

In the UK alone, more than 12,000 people have died or been removed from transplant waiting lists in the last decade without receiving the organ they needed, according to data cited by The Guardian. Similar patterns appear in many high-income countries, despite improvements in surgery and post‑transplant care.

Kidney patients are hit first. End‑stage renal disease can be managed for a while with dialysis, but that comes with harsh side effects, dependence on machines and a high cost for health systems. For some patients, the wait for a kidney stretches so long that their health collapses before a compatible organ appears.

For thousands of people each year, the problem is not that medicine lacks the tools, but that the right organ never arrives in time.

In that context, doctors and regulators have started to ask a blunt question: if humans cannot supply enough organs, can animals safely fill part of the gap?

From science fiction to surgery: why pigs?

The concept of using animal organs in humans, called xenotransplantation, has been discussed for decades. Early attempts using primate organs in the 20th century ended badly, largely because the immune system destroyed the grafts almost immediately. The field then stalled for years.

Pigs have now become the leading candidate for several practical reasons:

- Their organs are similar in size and function to human organs.

- They grow quickly and can be bred under strict medical conditions.

- They are already used to produce heart valves and some medical materials.

What changed recently is not the choice of animal, but the precision of genetic engineering. New tools, including CRISPR-based techniques, allow scientists to “edit” pig DNA with far more accuracy than was possible even a decade ago.

Rewiring the pig to calm the human immune system

For years, the main obstacle was the human immune response. As soon as a non‑human organ entered the body, antibodies and immune cells treated it as a hostile invader. The result was what surgeons call “hyperacute rejection” – the transplanted organ failed in hours or days.

Teams such as those at NYU Langone Health in the US have helped map out this reaction in detail. They have shown that certain sugar molecules and proteins on pig cells act like giant warning flags for the human immune system.

By removing or modifying specific genes in pigs, researchers can switch off some of the main triggers of rejection before the organ ever reaches a human body.

Today’s experimental pigs often carry multiple edits: some genes are knocked out, while others are added to make pig cells look slightly more “human” to the immune system. These modifications are combined with strong, but familiar, anti‑rejection drugs used in conventional organ transplants.

The goal is not to create a perfect match, which is probably impossible, but to reduce the immune attack to a level that current medicines can handle.

What a genetically modified donor pig might look like

| Feature | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Removed sugar markers on cells | Reduces immediate antibody attack |

| Added human immune-regulating genes | Makes the organ less “foreign” to immune cells |

| Inactivation of certain pig viruses | Lowers risk of cross-species infections |

| Breeding in biosecure facilities | Limits exposure to pathogens before transplant |

First operations: from theory to real patients

The earliest modern pig-to-human transplants focused on patients with no remaining options, often those too ill to receive a human organ or for whom a donor could not be found in time. These highly monitored cases are used to answer blunt questions: Does the organ function? For how long? What kind of complications appear?

Some trials have used pig kidneys, others pig hearts. In a few instances, organs were transplanted into brain‑dead donors maintained on life support, letting teams study organ behaviour without putting a living patient at fresh risk.

Results so far suggest that, under the right conditions, pig organs can work in a human body for weeks or even months, rather than failing immediately as they once did.

Researchers stress that this is still early-stage work. There are concerns about long‑term rejection, chronic inflammation and infection. Yet each operation provides data that helps refine the genetic designs and drug protocols for the next attempt.

Could pig organs reshape everyday medicine?

If these procedures prove safe and reliable, transplant medicine could shift from scarcity to something closer to planned supply. Instead of waiting for tragedy to strike a compatible human donor, hospitals might schedule a transplant in advance, using an organ from a purpose‑bred pig.

That would change more than waiting lists. It could also reduce the number of emergency surgeries, allow better preparation for patients and staff, and lower some of the logistical chaos around organ transport.

Kidney disease is the most obvious field for impact, because dialysis already strains budgets and patients’ lives. A predictable pool of donor kidneys, even if partly from pigs, could cut both mortality and costs.

Ethical and social questions that still need answers

Xenotransplantation raises questions that go well beyond the operating room. Some people worry about animal welfare in breeding genetically engineered pigs solely for parts. Others fear unknown infections, even though donor animals are screened and raised in controlled environments.

There is also the risk of unequal access. If pig organs become a commercial product, will they be available on public health systems, or mainly in private clinics and well‑funded countries?

Regulators, ethicists and patient groups are now debating frameworks for consent, animal care and oversight. Many argue that, given the current death toll from organ shortages, refusing to test this path would come with its own moral cost.

Key risks and why doctors are cautious

Researchers often group the main concerns into three categories:

- Immune complications: Even with genetic tweaks, the immune system can attack the graft over months or years, leading to chronic rejection.

- Infection: Pigs carry their own viruses and bacteria. Intensive screening and genetic editing aim to neutralise them, but long‑term surveillance of recipients will be needed.

- Unknown long‑term effects: No one yet knows what happens ten or twenty years after a pig organ transplant, because no such patients exist.

This is why early candidates tend to be people facing life‑threatening organ failure with no realistic human donor available. For them, the potential gain – extra months or years of life – may outweigh uncertainties that would be hard to accept for a stable patient.

What this could mean for patients and families

For someone newly told their kidneys are failing, the prospect of a pig organ can feel unsettling. Doctors report that when they explain the logic – engineered animals, strict infection controls, familiar anti‑rejection drugs – many patients become more open to the idea.

Families who have seen relatives deteriorate on waiting lists often view xenotransplantation in very practical terms: if it works and is safe enough, it is a chance that did not exist a few years ago.

For health services, pig organs could act as a pressure valve. Even if they never replace human donations, they may serve as back‑up options for the sickest patients, or as temporary “bridge” organs that keep someone alive until a human graft is available.

Concepts worth unpacking: rejection and genetic editing

Two technical notions sit at the heart of this story. The first is rejection. When doctors talk about it, they mean a spectrum of reactions. Hyperacute rejection is the immediate, violent one. Acute rejection happens over days or weeks. Chronic rejection can quietly damage an organ over years. Pig organs will need to pass all three stages to become a routine option.

The second is genetic editing. This involves changing the DNA of pigs in ways that persist through breeding – for example, deleting the gene that produces a sugar molecule humans react badly to. Each new edit can bring benefits, but also fresh questions, so the number and type of modifications are being adjusted from one generation of donor animals to the next.

As these techniques advance, doctors imagine a future in which organs are not only more available, but also tailored to typical patient profiles: hearts that suit smaller bodies, kidneys engineered to tolerate certain drugs better, or livers tuned for specific metabolic conditions. That scenario is still distant, yet the first operations suggest it may no longer belong only to fiction.