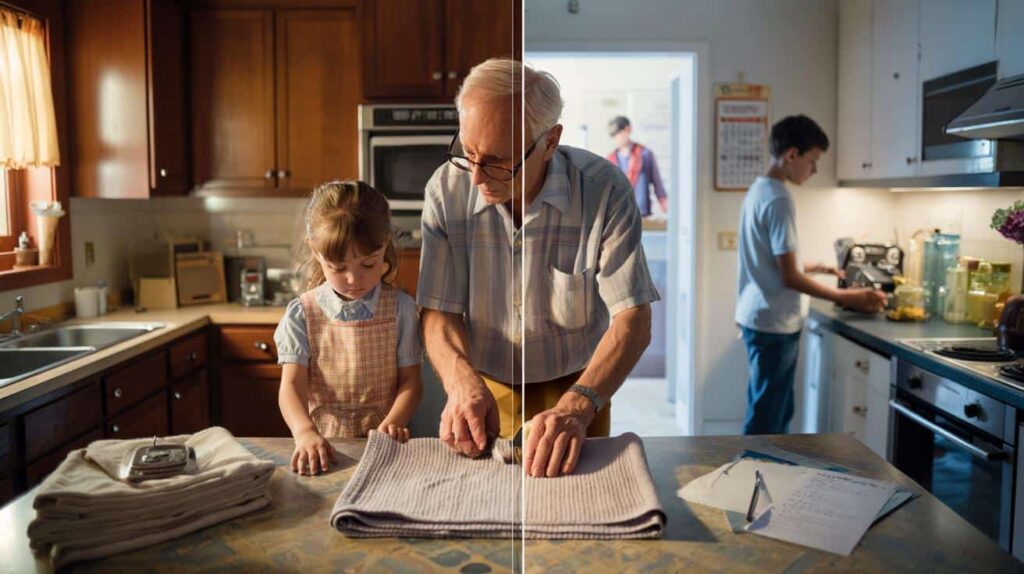

The other day, I watched a grandfather quietly show his grandson how to fold a worn cotton dish towel. Not just stuffing it in the drawer, but folding it in half, then in thirds, smoothing the corners with his palm. The boy looked puzzled, almost amused, as if this tiny ritual came from another planet. The grandfather didn’t explain; his hands did the talking. A rhythm from another time, another set of rules about how life should be handled.

If you grew up in the 1960s or 1970s, you probably recognize that rhythm. Life lessons were everywhere, baked into chores, routines, stray comments on the porch. Many of those lessons never made it into textbooks.

And quietly, they’ve slipped out of modern education.

The lost art of “figure it out for yourself”

In the 60s and 70s, adults had a favorite teaching method: they pointed, shrugged, and said, “Go on, you’ll figure it out.” No step-by-step explainer, no hyper-detailed safety briefing, no YouTube tutorial playing on the side. You wanted to fix your bike chain, bake a cake, call the utility company? You stumbled your way through, hands shaking, heart racing a bit.

That wasn’t negligence. It was a kind of rough-edged trust. The message was simple and brutal: the world won’t always hold your hand, so learn to walk without one.

Think back to your first solo errand as a kid. Maybe your mother pressed a crumpled note and a few coins into your palm and sent you to the corner store. No smartphone. No tracking app. Just your memory of the list, the route, and the unspoken rule: come back with the right change.

On the way, you learned to cross the street, talk to adults, read prices, count coins. You also learned to deal with fear — the big dog behind the fence, the older kids outside, the cashier who spoke too fast. That ten-minute walk was a full-life tutorial hidden in an ordinary afternoon.

Today, education leans heavily toward eliminating uncertainty. We give kids rubrics, checklists, multiple attempts, instant feedback, detailed scaffolding. It’s caring, and sometimes necessary. Yet something softer has vanished: that old-school expectation that you can operate with incomplete instructions and still land on your feet. When “figure it out” disappears, so does a certain kind of quiet inner confidence. The kind that comes from failing in small, manageable ways long before life hands you the big tests.

Respect, consequences, and the long memory of adults

Another lesson that used to be drilled in from every angle: respect isn’t optional. In the 60s and 70s, you didn’t call an adult by their first name. You didn’t interrupt grown‑up conversations. You didn’t roll your eyes and walk away mid-sentence without consequences. Respect might have been unevenly applied and sometimes too rigid, yet it formed a solid frame: there are lines you don’t cross.

School, church, the neighborhood — they all seemed to agree on this. Adults spoke with one voice. That echo has faded.

Picture a classroom in 1974. The teacher writes on the chalkboard, dust floating in the sun. A boy at the back whispers a sarcastic comment. The teacher stops, turns, and just looks at him. No shouting needed. After class, there’s a quiet talk, maybe an extra duty, a phone call home heard through the thin kitchen wall. The message is simple: words have weight, attitude has a cost.

Compare that with a modern classroom where the teacher juggles behavior charts, parent emails, and policy documents. Respect is now a topic for workshops and posters, instead of a daily drill lived out in small, firm interactions.

When respect becomes a formal curriculum objective rather than a lived community norm, it loses some of its teeth. Kids learn to say the right phrases — “I hear you,” “I understand” — without actually holding the emotional weight behind them. *Old-school respect wasn’t always gentle, but it was deeply anchored in the idea that you are not the only person in the room who matters.* That quiet boundary, taught early and often, shaped how you spoke to bus drivers, nurses, shop assistants, your own parents when they grew old. Its disappearance leaves a strange, floating gap where limits used to be.

Money, work, and the dignity of “good enough”

One of the most practical missing lessons is money. If you grew up in the 60s or 70s, you probably learned about earnings and limits the hard way. Want that new record, that baseball glove, that pair of flared jeans? Get a paper route. Babysit. Mow lawns. Clip coupons with your mother at the kitchen table. Nobody sat you down with a slideshow about “financial literacy”. Life itself did the explaining, blunt and non-negotiable.

You felt the weight of a dollar in your pocket because you’d stood in the rain or the heat to earn it.

We’ve all been there, that moment when your teenage self stood in a store, counting coins twice before getting to the counter. Maybe the cashier waited impatiently. Maybe someone behind you sighed. You still did the math, out loud, half‑whispered, trying not to mess up. Later, at home, your parent would half‑joke: “You’re broke already? That’s your lesson.” No bailout, no parental credit card, maybe a small advance with conditions.

Those tiny humiliations and victories trained you better than any spreadsheet. They etched into you that work and reward are linked, not assumed.

These days, schools sometimes cover budgeting in abstract: slides about savings rates, interest, income vs. expenses. It looks neat on paper. Yet what’s missing is the felt experience of work, of time turned into money, and money turned into choices — or into nothing when you spend badly. Let’s be honest: nobody really tracks every single purchase in a color-coded app for more than a few weeks. The 60s and 70s version of money education was rougher, but it hit the heart first, then the head. That sequence matters. It made “I can’t afford it” a normal, non-shameful sentence. A boundary, not a failure.

The invisible curriculum of home skills

Beyond school, there was the quiet “home curriculum”. Kids learned how to sew on a button, iron a shirt without burning it, cook a basic meal, read a utility bill. Often it wasn’t a formal lesson. Your mother would hand you the needle and thread, your father would show you the fuse box. You watched, fumbled, tried again. No YouTube, no Pinterest-perfect result at the end. Just a shirt that no longer gaped open and a light that worked.

Those small skills gave you a sense that the world was fixable with your own hands.

Many adults today confess they left home knowing calculus but not how to clean a drain, plan a week’s meals, or call the doctor’s office without anxiety. It’s not laziness. It’s a missing transmission. Their parents, rushed and stressed, sometimes did everything for them to “help”. Schools pushed academic content upwards, crowding out cooking, woodshop, home economics. By the time anyone realized what had vanished, a generation was already googling “how to boil an egg” at 25.

The old 60s-70s home training wasn’t glamorous. It smelled like bleach, dishwater, and Sunday roast. Yet it carried an unspoken message: you are capable of running your own life, not just your career.

“My mother would say, ‘If you can’t cook three meals and clean a bathroom, you’re not grown, you’re just tall.’ At the time I rolled my eyes. Now I hear myself saying the same thing to my kids.”

- Basic cooking: how to turn cheap ingredients into filling meals.

- Clothing care: washing, folding, mending instead of throwing away.

- Household admin: bills, appointments, simple repairs.

- Shared chores: everyone contributes, regardless of gender.

- Hosting others: setting a table, offering food, simple hospitality.

What we lost, what we keep, and what we could quietly revive

None of this is about worshipping the past. The 60s and 70s had shadows we should never romanticize — harsh discipline, rigid gender roles, whole groups of people left out of opportunity and respect. Yet inside that messy picture were life lessons that gave many kids a strong spine: resilience, practical autonomy, ordinary respect, the ability to handle boredom without a screen, to tackle a problem with what’s on hand.

Some of those lessons simply moved. Grandparents now teach them in small pockets of time. Scouts groups, community kitchens, makerspaces try to reintroduce them. But they’re no longer the default background hum of childhood.

Maybe the real question isn’t “Why did schools stop teaching this?” but “Where in our kids’ lives does this fit now?” Around the dinner table? In weekend routines? In small risks we allow instead of instantly preventing? You don’t need a curriculum guide to show a teenager how to read a payslip, how to apologize properly, how to sit with discomfort without running away. You need time, patience, and a willingness to let them try – and fail – while the stakes are still low.

If you grew up in that earlier era, you carry these lessons in your body more than in your mind. How you fold a towel. How you speak to a waitress. How you react when something breaks. Those quiet habits are a kind of inheritance. The interesting question is: which ones do you want to pass on, and which ones are you ready to gently retire?

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Everyday autonomy | Reintroducing “figure it out” moments in safe contexts | Helps children and teens build real confidence |

| Respect as a habit | Teaching boundaries through consistent, calm responses | Improves family dynamics and social interactions |

| Practical life skills | Cooking, cleaning, budgeting, basic repairs at home | Prepares young people for independent adult life |

FAQ:

- Question 1What specific 60s-70s lessons can I start teaching my kids right now?

- Question 2How do I encourage independence without feeling like I’m abandoning my child?

- Question 3Isn’t today’s world too risky to give kids the same freedoms we had?

- Question 4How can schools realistically bring back practical life skills?

- Question 5What if I never learned these lessons myself growing up?